The Enduring Lure of the Celebrity Autograph †

Man Repeller

2020

Why does anyone collect autographs anymore? To answer: scenes from a weekend spent at Chiller Theater, a New Jersey convention awash with obscure or nearly forgotten celebrities and diehard fans.

SCENE 1: THE MAIN LOBBY

Barbi Benton’s autograph is a thing of cosmic beauty. Rendered in cobalt-blue permanent marker, it is rich in the calligraphic flourishes of old Hollywood type, an object born to be framed. Bombastic capital ‘B’s double over themselves, somersaulting in a flurry of stylized swirls. The stem of a lower-case ‘t’ arches like a treble clef. An ‘e’ loops over with practiced ease, as though a dancer caught mid-pirouette. It is fortunate her signature is so impressive, because it cost me $40 dollars.

Benton is a former Playboy model, actor, and musician once signed to Hef’s Playboy Records, and like most missives from the sort-of famous, hers was both generous and vague: “To Laura, my new best friend,” the curly letters white-lied. I’d picked out a 1969 Macbook-sized Playboy cover for her to sign, stacked beside other printouts for sale. In it, a teenaged Benton was framed by a generic beachscape, lithe frame glistening with water droplets, a towel half-concealing her breasts. The woman who sat before me at a plastic expo table—wearing leopard trousers, leopard heels, and a Dynasty blowout—was framed by an orange MEET BARBI BENTON banner and a cardboard Cheerios box. To her right was singer-actor Danielle Brisbois, also signing pictures. To her left, a booth of slightly gnawed puppets and puppeteers from Hanna-Barbera’s The Banana Splits Adventure Hour.

Later that evening, one of the ageing puppeteers would pay $75 dollars to sit on Benton’s lap, and Benton, who has always known what makes a good picture, would position his nervous hands around her body: one on her waist, the other on her thigh.

SCENE 2: THE CORRIDORS

I was there, inside a red-brick suburban Hilton hotel in Parsippany, New Jersey, to see Benton—alongside more than 100 other hard-to-place celebrities plucked from the annals of TV and cinema—for the 29th Chiller Theater Expo (formerly Horrorthon), a highly-charged, if desultory emblem of American cultural fandom. Less zeitgeisty than this year’s inaugural BravoCon, and sans Comic-Con’s Marvel-esque drag, the weekend-long toy, model, and film convention still manages to pull a substantial audience, all mulling excitedly around the hotel in matching orange wristbands. Chiller is loosely curated around the horror, gore, and nightmare genres, but also around anyone famous who will agree to come, even if their connection to scary stuff is scanty. (Benton, for instance, starred in only one slasher film and a poorly-received Argentine-American fantasy flick called Deathstalker.)

That sense of vagueness pervaded the convention—and was the driving force that prompted me to attend. In an era when entire sub-economies are built on engaging audiences of micro-influencers, the notion of ‘fame’ is cloudier than ever, neither prescribed to certain occupations nor imbued with any sense of permanence. The thing Chiller made clear is what happens when you lose it, or at least feel it waning: You book a table someplace with a concentrated, interested audience, and cover it with signifiers from your fame’s apex—a time when it was crystallized and real.

Before I arrived, I studied the talent lineup—flush with former child stars, WWF wrestlers, horror and fantasy actors—on Chiller’s deliciously timewarpy website. Most of the homepage appears slightly out of focus, as though viewed through someone else’s prescription lenses. Blotchy subpage backgrounds mimic mottled hotel carpet (a venue preview). There is a visitor counter and nine different-colored fonts, including orange and fluorescent green. An animated ad links to the home of New Jersey’s ‘Bat Man’ Joe D’Angeli, whose logo resembles Marvel’s Batman, but also a clip-art American flag flapping in non-existent wind.

An FAQ list reminds prospective guests of the rules. You can’t smoke inside The Hilton anymore! You can’t “work for the tickets”; you need to buy them like everyone else. If your band would like to play at Chiller, as bands sometimes do, you can email links to an MP3/4 or mail in a CD or cassette for consideration.

The guestlist is formatted like a high school yearbook: photo, name, informational snippet. It included horror hostess Elvira, Mistress of Dark; 90210 starlet and reality TV bust Tori Spelling; five baseballers from Field of Dreams; seven castmates from Revenge of the Nerds; and the biggest-ever cast reunion from The Warriors. Tony Cox, the elf from Bad Santa 1 & 2 was scheduled to be there, along with Geri Reischel, who appeared as Jan on The Brady Bunch Variety Hour, and is known on the convention circuit only as “Fake Jan.” Also present: the actors who played young Jenny and Forrest in Forrest Gump; Lisa Loring, formerly a pigtailed Wednesday Addams; and British twins Carey and Camilla More, who jointly assumed the role of Days of Our Lives’ Gillian Forrester, but more importantly, Tina and Terri in 80s slasher Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter. I wasn’t intimately familiar with their franchises, but for some reason, that didn’t matter. I wanted to meet them all.

Strolling beneath the hotel’s fluorescent lighting, past bootleg DVDs and an autograph authentication desk ($10 dollars to check items signed at the show), Chiller looked like a cross between a costumed school reunion (steampunk glasses, top hats, near-constant embracing) and a car-park swap meet (ameteur art, muscle-men figurines, an out-of-place booth that seemed to be run by Hells Angels New Jersey). The main activities involved parting with cash: queuing for autographs in windowless rooms, imbibing at the lobby bar, buying memorabilia and macabre obscurities. I am now the owner of a Living Dead Doll named “Sin”; a smirking, purple-lipped clay clown; and a sexploitation film poster I’m still on the fence about, bought from a man known only as “The Professor,” whom I loved immediately, and who wore an I LOVE TO HURT PEOPLE badge, referencing the 80s wrestling documentary. (Regrettably, I did not buy a DVD entitled I Spit on Your Corpse.)

SCENE 3: THE BAR

Chiller attracts diehard fans, of both old movies and convention circuits. They seemed to mostly be in their 40s or older, meaning those who’ve attended for a decade (I’ll remind you this is the 29th edition) can still be deemed newbies. I learned this from Eric, a redhead documentary-maker outfitted in a splatter suit, who carried a pair of drumsticks, but no drum, and had been coming since 2003. (Like a lot of people I spoke to, he lives in New Jersey.) “Every time I walk through the main hallway here, I see someone and say, ‘I remember you from two years ago!’ Or even six months ago!” he told me. “It’s crazy. The niftiest thing about Chiller is that everybody is almost automatically friends. You think, ‘Oh, you’re a fan of Roller Boogie and Death Zombies? You’re a fan of movies that are obscure, but also really popular? And you’re a fan of dressing kind of weird, even when it’s not Halloween? Me too.”

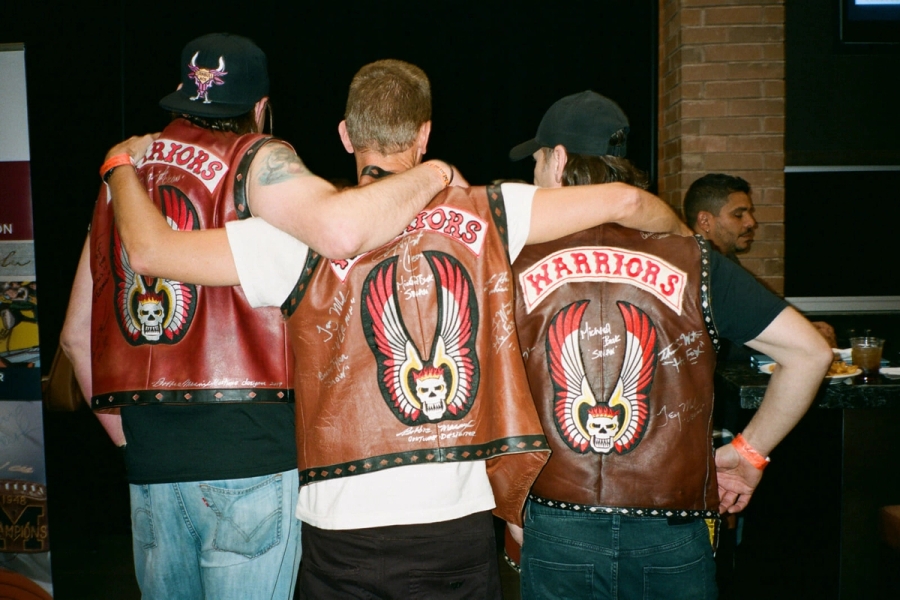

Eric and I convened in front of the bar, where a lot of people met between bouts of sensory overload: swapping intel about guests and reveling in nostalgia, letting it swallow them whole. (As one guy in blue jeans mock-lamented, “I have more stuff than I can sell, more movies than I can watch, more posters than I can hang—but I keep coming.”) The bar is like most bars in America, except there’s always a seat, the air-conditioning is set to freeze-blast, and a substantial portion of patrons at any one time are outfitted as the fictional gang from The Warriors (released in 1979).

Photo by Poppie Van Herwerden.

Three of these faux Warriors—wearing leather vests scrawled on by cast-members in fat silver marker—had traveled together from the UK. After the convention, they planned to make a pilgrimage to Coney Island, retracing the steps of the filmic Warriors, on the run from rival gangs. Right now, they were drinking beers and taking photos with strangers: mini celebrities in their own right.

As a special festival flex, the bar served custom cocktails—The Chillers—advertised in a font that simulated knife slashes. There was a Trick or Treat Punch, “back by popular demand and … frighteningly delicious,” an amaretto on the rocks topped with Sam Adams Octoberfest™ beer, and a creamy drink named The Forrest Gump that was “Like a box of chocolates,” a line I’d seen around the same time on the tablecloths at Bubba Gump Shrimp in Times Square.

SCENE 4: THE CAR PARK

The weekend’s climax was a fire drill. As a shrill alarm sounded, fans and stars alike lurched outside begrudgingly (“This happened last year! We’ll be out here for hours!”), and waited together between parking spaces, trying to make the best of it. The spectacle was sublime and sobering, reminiscent of the moment all the lights flicker on at a club, and you can actually see the muddled cast you’ve been pressing up against. For a while I drank moonshine offered to me from the car trunk of three strangers in their sixties, who’d traveled cross-country to get some autographs, and were just happy to be there. Two of them were madly making out during a lot of our conversation—later revealing they’d only met the day before—and the third wheel, who wore a flapper dress, told stories about her daughter between swigs, a massive purple feather quivering in her cap.

All around us, over asphalt, meet-and-greets resumed—though without the tables, it was hard to discern who was actually a celebrity. My friend got a photo with a Sopranos star, who afterward said he’d been charging $40 dollars for photo ops inside, but the $20 dollars in her wallet would do. I got a (free!) photo with a guffawing Jeremy Woodworth—he played John Wayne Gacy in The Killer Clown Meets Candy Man—who scrunched up his eyes while scratching at his crusty, ruffled suit, pinned with brightly-hued badges that read WANT TO CUDDLE UP? and LEAD ME TO YOUR TAKER.

What is it that compels us to not only meet the semi-famous, but secure evidence of our brief interactions? I’d wondered this inside too, as WWF wrestler Greg “The Hammer” Valentine signed a topless picture for me and made polite small-talk, his table cluttered with soda cans. I’ve never liked approaching people I admire outside of an interview—on recently noticing Patti Smith beside me at a bookstore, I froze—but at Chiller I stacked up signatures like it was my job. Perhaps it was the context. Against the dated aesthetics of the Hilton Parsippany, encounters with fame were straightforward and transactional; there were venue maps and prices and a print-out schedule indicating who was willing to see you and when. The chance to engage with an object of prolonged fetish up-close, to collapse or fracture the boundary between the imagined and real, assumed refreshing banality in the convention format. If you wished to participate in a Q&A with the actress Nancy Allen, you could visit The Hydrogen Room at 2 p.m. If it was packed, you might form a teller line, just like at Citibank.

“You used to be able to videotape,” one guy told me outside, clasping a signed photo closely to his shirt. You could even film your own interviews for free at one point, he said—now Chiller charges $50 for taping privileges. He still finds a lot of beauty there, even if it costs. When you hear the real, live voices of those you’ve loved on the big screen, he says there’s a sense of being transported to an alternate reality, of tearing off an expiration date, reanimating memories. His interest began with Petticoat Junction, a CBS sitcom he’d watched growing up with his father. Following his dad’s death, he wanted to meet the actors, and add to a moment that had always felt good and true. Now, he says, working as a dump truck driver, the prospect of escapism remains compelling.

Unlike the real fans, I hadn’t gone to Chiller with precise scenes from my own life I hoped to revisit, or a checklist of celebrities. Everybody thrilled me, looking like uncanny valley versions of their younger movie selves. I’d wanted to meet Robert Wuhl, whose program picture resembled a LinkedIn display photo, and who seemed to encapsulate the slippery, nebulous nature of notoriety: how much easier it was to orbit around than hold in your two hands, how decades later, everything you worked for could boil down to a few scant IMDB credits and a regional convention table. Wuhl played “man with lighter” in 1995 flop Dr. Jekyll and Ms. Hyde, “Mawby’s regular” in Flashdance, and, most famously, reporter Alexander Knox in Tim Burton’s Batman. I wondered if he ever rewatched them.

I never did meet Wuhl, but I kept seeing The Warriors—not the 13 cast members, who were stationed in the Cobalt Room—but their British body-doubles. The two gangs had a symbiotic relationship: each required the other to relive moments of glory. As the festivities wound down and mini-stalls shuttered up, I watched the fake-Warriors collide with their idols. They were all in the Cobalt Room, which was almost empty, packing down plastic tables together.